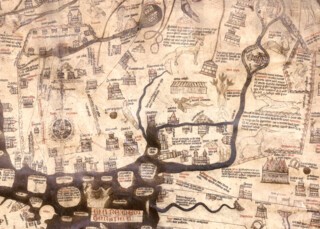

Seven centuries ago, an artist made a perforation with a compass on a large piece of parchment. The pinprick formed the centre of his universe. Around it he drew the circular shape of a city, with crenellated towers – Jerusalem. Radiating outwards from this point, the artist and perhaps six others portrayed the world as they knew it. It was a circular world, hemmed by a great ocean. They drew distant and fabulous places – Troy, the Red Sea, the Cretan Labyrinth – as well as some less fabulous ones, such as ‘Carlua’ (Carlisle) and ‘H’ford’ (Hereford). The parchment is now known as the Mappa Mundi and it can still be seen in ‘H’ford’, where it was probably made around 1300. It is worth the visit just to see the tiny pinprick at the map’s centre, an in principio moment visible centuries later.

‘Mappa Mundi’ can be translated as ‘map (or cloth) of the world’. Cloth might be more appropriate because the Mappa isn’t a ‘map’ in the way we would now understand it. It wasn’t made to show you the way to anywhere, except perhaps to heaven. It describes both space and time, biblical history, classical mythology, spiritual truth. Maps often tell us more about their makers than they do about the world. Modern European maps, for example, put Europe at the top and centre. Medieval European maps put our north to the left, east to the top and south to the right, with Jerusalem at the centre. In the bottom left-hand corner of the Mappa Mundi, at the world’s edge, there are some blob-like islands – Anglia, Scotia, Hibernia – but not much is happening there. A little further away, however, towards modern-day Norway, we see a figure, labelled ‘Gansmir’, in a pointed hat wearing a pair of skis. An inscription reads ‘super egea currit’ (‘he runs along egeas’), which shows an unfamiliarity with skis or Latin or both. It’s possible that it is meant to read ‘super aquas current’ (‘they will run upon the waters’).

Not far from Gansmir, in the region roughly approximate to western Russia, we can see a large bear; it has an almost embarrassed expression. A little further on, east of Hungary, we find an improbable ostrich. The inscription reads: ‘Ostrich: head of a goose, body of a crane, feet of a calf; eats iron.’ Pliny the Elder said the bird ‘has a remarkable ability to digest anything it swallows’. This Europe is not one we would recognise. It is principally defined by its water systems; our modern borders are nowhere to be seen. A mermaid swims in the Mediterranean.

Some of the creatures have recognisable names, but would be hard to identify in a line-up. The crocodile looks more like a cow wearing a lizard mask. It is being ridden by a man wielding an axe. Hugh of St Victor claimed that the inhabitants of ‘Meroe’ in the Nile domesticated ‘cocodrillios’ and rode them across the river. Other creatures are entirely unmoored from reality, like the manticore, which supposedly has a ‘triple set of teeth, the face of a human, yellow eyes … a lion’s body, a scorpion’s tail, a hissing voice’, but is depicted on the map with a sleek, leonine body and the face of a surprised-looking man, with a short beard, wearing a crown. The fabled sets of teeth aren’t visible. In the upper reaches you can find the bonnacon – a benign beast with the paws of a leopard and the body of a bull, its horns curving inwards. The bonnacon is shown expelling faeces, a feat which, the inscription notes, it commonly performs in self-defence.

The map’s humanoid creatures are some of its most compelling. There are dog-headed men (seemingly engaged in conversation) as well as a ‘monocule’ or Sciapod: a man with only one foot, extended into the air. He cuts a lonely figure, as does the Blemmye, a creature with no head but a ‘face’ in the middle of its body. In a region between Armenia and China (near neighbours in this rendering) we can see a stork person, with a human body, stork’s feet and a beak on its human face.

As well as places and creatures, the map also shows events: the expulsion from the Garden of Eden; the quest for the Golden Fleece; Noah’s Ark filled with humans and beasts. And beyond the circular edge of the world, events both within and outside time occur: the Last Judgment at the top and, in the right-hand corner, a huntsman on horseback, departing the scene. He is followed by a forester and a dog. The forester addresses him, ‘passe avant’ (‘continue on’), but the huntsman looks back wistfully at the universe above him. Some scholars think this scene refers to a specific historical incident involving Bishop Thomas of Cantilupe, who was a keen huntsman, but I prefer to see the rider as allegorical, a figure who searches for salvation in the heavenly realm and is exhorted to leave the sinful world behind.

The passage of the centuries has etched new biases and alliances on the parchment. The town of ‘H’ford’ is nearly rubbed away, presumably by generations of visitors who jabbed at the map to mark their place in the world (a familiar impulse). The area of Paris and France, meanwhile, has been scored by a knife. Nineteenth-century scholars, among them the authors of Medieval Geography (1873), believed this ‘might have been perpetrated by some over-patriotic Briton at a time when feeling ran high against France’. This impulse might be familiar to some, too, but the diagnosis of ‘feeling … against France’ reflected their own mentality. The last time I visited the map at Hereford Cathedral, I passed a sign outside a pub that read: ‘Brexit Beer Deal: Tell the Bar Staff What You Want and Get Something Completely Different.’ Hereford voted overwhelmingly for Leave.

Maps and their ghosts remind us that our sense of the world, and our place within it, are contingent. The Mappa Mundi is the largest surviving medieval map. An even greater mappa mundi, the Ebstorf Map, was destroyed in the Allied bombing of Hanover on the night of 9 October 1943. It survives only in black and white photographs and some disappointing colour facsimiles.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.