Many of the works in The Making of Rodin, currently on show at Tate Modern (until 21 November), are displayed on what look like the packing cases in which they arrived. A notice on the wall tells us that these supports, and the Perspex boxes containing the sculptures, will be reused in future exhibitions and in construction projects at the gallery. Exposing the hardware is a way of acknowledging the environmental cost of transporting and displaying art. It also catches the provisional mood of the past eighteen months. As a curatorial gambit, it’s in line with the objects these rough plinths support: Rodin swings between the ephemeral and the monumental, and many of the sculptures here were first displayed on little more than bare boards. Almost all of them are made of plaster, their fragility contrasting with the heavyweight bronze or marble forms into which some of them were later developed. The packing boxes show that these are objects on their way to somewhere else, or to becoming something else.

In 1900, as his celebrity boomed, Rodin organised a display of his work at the Place de l’Alma to coincide with the Exposition Universelle. A specially constructed pavilion with high arched windows, a glass ceiling and adjustable blinds showed the sculptures to great effect, allowing the play of natural light on their surfaces. Visitors were confronted with an all-encompassing whiteness, the fine dust of the studio filling the air. This was Rodin’s first one-man show in France, but he had posterity in mind: he called it his ‘museum’. The pavilion came down in 1901, but Rodin soon reprised the show at his home in Meudon, just outside Paris, where he had kept a studio since 1893. It is now the Musée Rodin, from which almost every work at the Tate has been loaned. Rodin bequeathed it all to the French state in 1916, the year before he died. The bequest established material genealogies for each of his ‘finished’ sculptures; it also helped to produce a shift in taste towards the more provisional objects Rodin made in advance, which gradually came to be seen as artworks in their own right.

Plaster, with its preparatory or partial quality, had a particular appeal in the decades after the First World War. And it’s this that makes Rodin seem so modern, almost one of our contemporaries. Lighter, more playful, and alert to accidents of making, the plaster sculptures are closer to present-day aesthetics than the works in bronze. These are part-objects, remodelled, transformed, transitioning. The artist Phyllida Barlow compares plaster’s paradoxical combination of substance and transience to that of snow. Yet in the 1900 show, from which the Tate exhibition takes its cue, Rodin exercised an unusual degree of control over the work’s display. He chose each piece and its socle, and by crowding them together to suggest the artist’s studio – or an aestheticised and tidied-up version of it – he appeared to offer real access to his process. Rodin would have approved of the current exhibition. Blinded by whiteness, we approach the assembled limbs and contorted faces ready to relearn old lessons about transcendent material transformation.

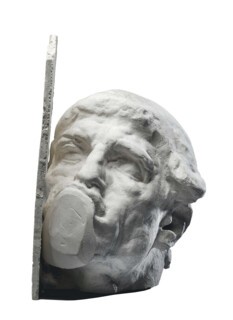

One of the first works in the show is both familiar and very strange. The head of The Thinker, detached and upright, has its right side pressed to a plaster surface, into which a hole has been cut to reveal the ear. The fist on which the chin will later rest is here just a rude plaster plug, blocking and silencing the mouth. It’s a remarkable object, radiating violence. There are echoes of Duchamp’s With My Tongue in My Cheek, but the shock comes from something far more direct: a severed head, the stuffed mouth a final humiliation. One of Rodin’s talents was to let you see the brutality of making sculpture.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.