Pitt Street in Wellington runs just below the crest of a ridge. It is steep. When you look up to the houses, you don’t see much more than roofs. To reach the front gates you take paths that angle up the ten-foot clay bank that was cut when the road was made. The land seems less stable than the timber-framed houses that sit like ships on a sea of clay and rotten rock that after a week of rain slides below them in slow motion. In the old days, after several wet weeks there would be landslips in the cuttings that took the tramlines down to the promontory where the line comes into the open at a point on the fault scarp (it shows on the map as a ruled line along the west side of Wellington Harbour). You are still high up when you emerge from the cutting: it was (and is) a wonderful grandstand. The land feels eager to be eroded all over New Zealand. Charles Andrew Cotton, a local pioneer of geomorphology could illustrate most generalities of what erosion does to landforms with native examples.

All my New Zealand years I lived at 13 Pitt Street with my parents and sisters. (As you walk down, the odd numbers are on the right – the east side.) My memories all gather round the house, and the roads that took you away from it: down through the cutting to the city, over the hills to Karori or out to the bays. The hilly landscape was like an illustrated map. From the living-room window I could look down or across at the houses of friends of my parents. From the knoll at the end of the cutting I could see the ferries cross the harbour and turn westward to escape the encircling hills as they made for the South Island.

The weather was not blandly seasonal. It was rarely very cold – the native bush is evergreen – but the weeks of rain, cloud and wind were punctuated by days of bright, windless sunlight, the air cleared to such perfect transparency that the distant perspective was veiled in blue mist as in much European painting. At the end of the day it could go yellowish. Sometimes a Canaletto reminds me of home. Out of town at the beach the sun heated bare sand to the point that you had to skip through it or burrow down into the cool layer below. The climate was not enervating, weather changed fast.

The ingredients of the landscape which still sit firmly in my memory are, first, the hills. Burned and cleared at some point in the past (the near past: not much longer ago than the seventy years I have lived), they had been made into farmland – sheep runs mainly. Only the steepest gullies were still the dark, muddy green of the native vegetation; the low, dense covering of ngaio and rangiora, lance wood and manuka, was a reminder of how the land had looked when first settled. As the farmland became unprofitable or unmanageable, gorse, broom and blackberry took over. There was much light and much wind. In summer gorse fires threw up dense billowing columns of brown smoke, broken by bursts of orange flame. The fire engines came, another patch of blackened hillside was born, but the houses seemed to withstand it – the thin, dry furze must have flared up and then quickly died down. When my parents gardened on the steep bank that ran down from the strip of fenced lawn (they inherited a garden roller when they bought the house: a real lawn was intended), they grew the roses, pinks, irises, canterbury bells, ixias and poppies of an English border. Some of these plants (they were not native to England after all) did rather well. The clay suited roses. But the wind cut and bent any shrub that reached up to make a pretty shape of itself. Yet my mother kept flower vases full, quite grandly sometimes.

The house was not well planned. It was orientated to face the triangular scrap of harbour you could see to the north-east, so a narrow path led down the side to the front door and the front porch – big enough to sit in. Beyond the dining-room was a kitchen that was also the corridor to the bathroom, the children’s bedrooms and the back door, which opened onto a space with the lavatory off it on one side and the washhouse on the other, with its copper sink, filled and emptied by hand, but cherished by my mother as a place to burn bundles of rubbish. Sheets were boiled in it, turned with a stout stick that soap and hot water slowly disintegrated. The last time I saw the place new owners had substantially rationalised it.

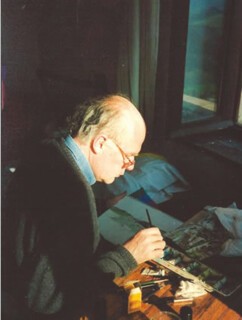

It was, I now realise, a physical environment that would have been recognisable as that of a liberal, left-wing intellectual. Osbert Lancaster could have put the decor into a Hampstead Garden Suburb drawing-room. The bedroom suite, the dining-room furniture and my father’s desk were copied by a local cabinetmaker from a Heal’s catalogue. The red spines of the Left Book Club (many faded pink) and the blue volumes of Proust were on the shelves. The pictures were prints: Franz Marc’s Tower of Blue Horses; a Monet of yachts on a river; Duncan Grant’s Dancers, a cornfield by John Nash. The one original was a watercolour by T.A. McCormack dominated by a Chinese fish plate. Over the years all this moved towards something prettier; the first impulse to modernity was not wholly sustained.

Happiness was a professional matter because I come from a family of teachers and ‘educationists’. That is how I described my father’s profession on forms at school. What did it mean? More than being a teacher, because while he had taught he had also lectured at the university; his MA thesis was on ‘The Laughter of Children’, and from 1939 until 1952 he was director of the New Zealand Council for Educational Research, which was founded with seed money from the Carnegie Corporation. The council published books and reports (our first supply of drawing paper was proof sheets). It also supervised the distribution of Binet IQ tests to schools. My sisters and I were checked out – I have a vague memory of a trip to the teachers’ training college to take the test. We were not given the results, but somehow assured we were bright, something over the average. We used to visit Dad in his office, and I remember looking through the illustrated books on children’s art, sitting in the revolving chair, being talked to by Ilse Jacoby, my father’s secretary.

Ilse was one of that cohort of refugees from Germany that did much to transform intellectual life in New Zealand. Her husband, Peter, worked as a statistician in the Education Department. There were also the Dronkes, the Steiners, the people who founded the chamber music society. There was Karl Popper. Mostly they were reduced to doing jobs nothing like as responsible as those they had left. Popper, at Canterbury, objected to teaching basic logic, but he and others, like Peter Munz who worked at the university, had an easier time of it than some. Peter and Ilse lived in a small house up on the hill in Karori; it seemed a more delicate and sophisticated environment than ours. Peter was, I think, a political scientist; there were early editions of Thomas Hobbes on the shelves. Ilse typed up John Beaglehole’s edition of Cook’s journals. Only occasionally did my father seem to feel that the refugees might have been a little impatient with provincial life in the South Pacific.

My friend Graham Percy (who came from Auckland) talked about us as belonging to the Wellington mandarin class, but within that class there were divisions. My mother didn’t, and I think didn’t want to, join the university wives who walked and talked and lunched together. Her taste in friends was hard to characterise. There was Beatrice Beeby, the wife of my father’s boss in the Department of Education, who became New Zealand’s ambassador to France (as his son did after him) and a figure in Unesco. Beatrice was thin, elegant, and to my eye glamorous and amusing. Beeb was funny and clever. My father was very much in his shadow, much less flamboyant. When he took over the job of director of education my guess is that he was better at doing the things Beeb found boring.

My education began at the infant school housed in the church hall at the top of Pitt Street. The teacher, Mrs Stone, was known to use the strap. Family principles about corporal punishment were strong, and doubtless a reason for our being transferred (were strings pulled?) to the school attached to the Kelburn Teachers’ Training College. But I can remember a few scenes from what was, I guess, my first year at school. First being given a hint by Mrs Stone that I should be playing with the boys not talking to the girls; then an air-raid drill where we lay in a ditch – we must have been issued with iron rations of some sort because I remember a small cake of chocolate.

It is from Kelburn that my first memories of the children I was taught with come. Particularly the girls – Libby Gordon, the Priestly girls, so pretty and talented. The boys – Alistair Scott, for example – vaguer. But I do remember wrestling with Alistair in the school playground – to what end, and for what reason if any, has long gone. The composite class I was in for the last couple of years was used as a choir for school music broadcasts. Tommy Young had selected choir members, but his successor, Leslie Souness, wanted the full democratic sound of an entire class. Except me. I’ve always wished I could sing. I had a stammer too, so, unlike my cousin Keith and Barbara Ewing, the daughter of John Ewing who worked with my father, I was not recruited to be a Quiz Kid (I read Salinger’s stories with some interest). Perhaps it would have taken nepotism a step too far – my Aunt Jean ran Broadcasts to Schools. It was a small world in which connections were easy. Jean married, quite late, Des Buckley, the brother of Pat Hattaway, the editor of the government’s School Publications for whom I did many illustrations later on – making a substantial contribution towards the cost of the ticket to England. Was it corrupt? I like to think not, but it was certainly supported by family connections.

School is harder to remember than time out of school. Reading, drawing, walking – solitary things – and listening to adult conversations. Particularly my mother talking to her friends and to us. And there were holidays. At Raumati, thirty miles up the coast, Dad helped his father build a beach house – a bach. The red corrugated iron shed they put up first (my guess is that they had help with the framing and that Dad and his father did the lining and finishing), still with its bench and tools and earth (well, sand) floor, went on being used as a changing hut. The bach itself was small, even imagination can’t deny that. A kitchen, a bunk-room (the two upper bunks were preferred, but I fell out one night and was not allowed them after that), a living-room and a bedroom with a round porthole of a window, a conversation piece. Two water tanks took rainwater off the roof. The loo was a long drop under the pine trees that separated the bach from the hollow, a dip in the terrain that reminded you that you were perched on sandhills. It was passing bliss. The last time I saw the bach – it and its long half-acre had been sold – the area between the building and the sea, with its yellow tree-lupins, flax and toitoi, had been eroded back almost to the front wall. We had pushed past the lupins to a clear crescent and a wooden seat which faced the sea and the long hills of Kapiti Island. (I didn’t find out until we flew over it on a flight home many years later that its far side had eroded too, but into proper sea cliffs.)

Nearly always the holidays were shared with my Uncle Ian and his family. I can’t remember at all what the adult sleeping arrangements were – I guess the living-room was given over to one couple. And there were tents too. Washing was done in enamel basins, filled with the precious rainwater that dwindled all summer, tested by tapping the tanks. I don’t know how many Christmases we had there, but one I can date because I got the Phaidon book of Rembrandt drawings I had asked for, and my name and the date 1949 are on the flyleaf. I remember doing a drawing which I had labelled ‘after Rembrandt’ of which my Uncle Ian said: ‘A long way after.’ I reckon he thought I was given too high a notion of my talents. Very likely he was right. Another time, during a sleepover at their Karori house, I had packed a book called The Man Who Asked Questions, an introduction to Socrates for children. I found at his house a Classic Comic – maybe The Hunchback of Notre Dame – and heard some laughter from the next room when I took this for my bedtime reading.

The character of the two households was very different, though each in its own way academic. Ian became a professor of law at Victoria University, a rather fierce but much respected teacher. Arnold, my father, went from teaching at school and university to the NZCER and then the civil service, first as an inspector. He said that he wished he had been named not after Arnold of Rugby, but after Matthew the poet – also an inspector of schools. Ours was the less academically stressed family; I might now have better French, Latin and maths had it been more so, but I think my dilettantish character, noted on a school report, was native. The other household put great value on degrees and grades. My mother was a typist working in the Native Trust when she married my father. Ian was known to have said that he could never marry a woman who did not have a degree.

My mother’s father, Frank Livingstone Combs (usually called FL), was a teacher too, eventually headmaster of a school over the hills from Wellington in Featherstone, and a writer; he had a collection of essays published by Dent in London. He called it, against his publisher’s advice, The Harrowed Toad. The pieces are about children and teachers, and while the Kipling quotation (‘the toad beneath the harrow knows exactly where each tooth-point goes’) may have been apposite, it went along with the lugubriousness that had him signing himself ‘oldtimer’ at 30. He was also president, or some such, of the primary school teachers’ professional association.

My father’s father, Fernly Charlewood Campbell, was again a teacher and headmaster of a primary school. He was tall, thin, and as I remember him, an autodidact, learning French in his old age, gathering books around him. My father’s mother committed suicide – I presume clinically depressed, at least I never heard of any other reason, nor even of that one. When my cousin Donald killed himself I remember the intrusive family doctor arriving to tell us it wasn’t inherited. Who knows, although his bustling ins and outs didn’t reassure then (or at other times). But he was the one who diagnosed an ear abscess I had that might have been fatal (the current GP had gone off to the beach for the weekend), so we owed him – and his gossip filled in gaps in my mother’s life, even as she complained.

The primary school years and the later ones at Wellington College have left scattered scenes, but I was a dedicated non-participant. There was a holiday with my friend John MacKay, for example, whose extended family farmed grass (chewings fescue: fine grass for golf course greens). I remember combing the farmer’s wife’s abundant reddish hair, and somehow being implicated in a cruel tease by the woman who had driven us from Dunedin. John and I went out with .22 rifles and failed to get rabbits. I caught mumps and spent a couple of weeks in bed, turning the sepia pages of an interior design magazine and reading the novels of Georgette Heyer. This was the unsubstantial female part of a life dominated by men, sheep, scones for the shearers, lamb chops for breakfast and the leg for supper. Much more my kind of thing.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.