In Brussels

Erin L. Thompson

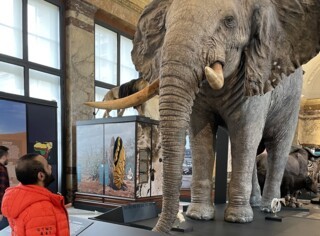

‘Why are you crying, habibi?’ Mansoor Adayfi asked the elephant. He had got into the habit of talking to animals at Guantánamo Bay. Held in solitary confinement for years, he talked to the feral cats who prowled around his cage.

‘I think that’s the glass eye shining,’ I said. We were looking at taxidermy displays in Belgium’s Royal Museum for Central Africa. We had come to Brussels for the opening of an exhibition he’d curated at the European Parliament, of artwork made by Guantánamo detainees. Last year, after the first time Mansoor spoke at the parliament, a friend had taken him around the tourist sites. They had ended up in a schlocky medieval torture ‘museum’ and Mansoor had posed for a photo with his hands shackled and hoisted above his head. ‘I knew how they felt back then,’ he told me, laughing.

This time, he posed next to the elephant. Born in a village in Yemen, Mansoor was nineteen years old when he arrived at Guantánamo. He spent nearly fifteen years there without ever even being charged with a crime. Released in 2016, he was sent to Serbia rather than being allowed to return home.

After years of trying, Mansoor had only just succeeded in getting a passport. He was wearing an orange puffa jacket that had been given to him during a recent trip to Ireland: it had ‘Close Guantánamo’ embroidered on the back and ‘GTMO 441’, his prisoner number, on one arm. In later years, Mansoor had become friendly with some of the guards. Following regulations, they called him by his number, not his name.

In Ireland, Mansoor had visited the graves of Bobby Sands and other hunger strikers. He told me the English technique of forcing a wooden bit between prisoners’ teeth – introduced for the suffragettes before the First World War, and still used on IRA prisoners in England in the 1970s, though not in Northern Ireland – was crueller than what he gone through when he was strapped into restraints and had a feeding tube snaked down his nose. But his jailers yanked the tube out painfully when they were done.

‘Where did they get him?’ Mansoor asked about the elephant. The museum has a temporary exhibition about the sources of its collections. Seventy per cent – more than 84,000 artifacts – were taken from what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo between 1885 and 1960. QR codes throughout the museum let visitors pull up more information about how a mask had been plundered by a colonial military commander during a punitive expedition, or a necklace had once been worn by the wife of a chief before he grew resistant to Belgian orders and was executed.

‘He must have died in some zoo,’ Mansoor guessed as I skimmed the page about the elephant.

‘Well, not quite …’ I hesitated. This trip was turning out to be not much better than the torture museum. ‘It says museum scientists shot him in 1954.’

‘Shot him? Why?’

‘To bring him back here, so we can look at him.’

‘My friend,’ Mansoor said to the elephant, ‘you had a problem even bigger than Guantánamo.’

I have known Mansoor since shortly after his release. I was putting together an exhibition of art from Guantánamo. His lawyer, Beth Jacob, put us in touch, and Mansoor wrote an essay for the catalogue. His memoir, Don’t Forget Us Here: Lost and Found at Guantánamo, was published in 2021. This was the first time we had met in person. Mansoor told me that I, like the elephant, was taller than he had expected.

We left the museum and went to the room at the European Parliament building where a few dozen paintings and drawings created at Guantánamo had been pinned to the wall. One was of a kneeling, shackled figure in orange. Mansoor keeps in close touch with its artist, Sabri al-Qurashi, also from Yemen but now stranded in Kazakhstan. Mansoor was wearing an orange T-shirt of his own design, printed with the image.

People arrived for the opening and asked Mansoor the questions people always ask.

‘How did you end up there?’ Since no charges were filed against him, Mansoor still can’t be exactly sure what the US authorities thought he had done. Like so much else about Guantánamo, it’s classified. Mansoor was detained while travelling in Afghanistan. From stray comments made by his interrogators and the trickle of information from the government during his release hearings, Mansoor thinks someone simply saw a chance to claim some of the money being offered by the US after 9/11 for al-Qaida suspects.

‘Did you meet any real terrorists there?’ Mansoor pointed out that 730 of the men detained at Guantánamo were released without charge, often after years or even decades. Of the thirty men who remain (at the cost of something like $445 million a year), sixteen have been cleared for release and are waiting for a country that will agree to take them. Ten are awaiting trial. Only one has been convicted.

‘Have you forgiven them for what they did to you?’ ‘No!’ Mansoor said, then laughed. He’s never had the chance to forgive anyone, since no one who wronged him has asked for forgiveness, much less shown remorse.

Alka Pradhan, who’s been defending Guantánamo detainees for a decade, first at an NGO and now as a human rights counsel appointed by the Department of Defense, showed me the fabric bracelet printed with a map of the island she had bought at the base gift shop (yes, it has a gift shop). A few years ago I told Pradhan I was relieved that at least we had stopped sending more people to Guantánamo. ‘That’s because we started killing suspects with drone strikes,’ she explained.

‘When are they going to give everything back?’ Mansoor had asked as we left the museum. So far, Belgium has returned only a single artefact to Congo, granting an ‘indefinite loan’ of a mask that had once been regarded as a source of power in battle. Such venerated objects were targeted for colonial-era seizures to undermine the authority of local leaders.

At least the museum had records to show where the mask came from. Many artefacts entered the collection with no information about their source at all. In part this is because King Leopold, when he handed his private colony over to the Belgium state, ordered that the records of his administration be destroyed.

‘Secret! It’s secret!’ Pradhan’s clients tell her and her fellow lawyers when asked how they baked a braided round of bread the size of a tabletop, or fried something when they don’t have metal containers, or managed to produce cheese. If the state won’t disclose the many secrets it keeps about them, the detainees won’t disclose their secrets either. (The attorneys guess that the cheese is probably strained through socks. They say it is delicious.)

The sponsors of the exhibition invited us to an afterparty, described as a ‘Guantánamo jazz night’. Mansoor, who does not drink and was tortured with loud noises, politely declined.

Comments

Login or register to post a comment-

27 April 2024

at

2:28pm

Delaide

says:

There are doubtless legitimate reasons but still it would be nice to know why he was travelling, at such a dangerous time, in Afghanistan. It’s a long way from Yemen.

-

28 April 2024

at

10:09am

ali almaadeed

says:

@

Delaide

Thanks for providing us with a good example of ‘Just Asking Questions’, or JAQing off. In other words, attempting to make accusations acceptable (in this case justifying torture) by framing them as questions rather than statements, thus shifting the burden of proof.

-

29 April 2024

at

12:43am

Delaide

says:

@

ali almaadeed

And thank you Ali for ‘JAQing off’, very good. I fear I am up against a formidable interlocutor. I did feel a bit uncomfortable asking the question but being a natural iconoclast (I think I can use that word) I couldn’t help myself. I was however only referring to why he was originally detained. I wasn’t implying a defence of his subsequent rendition and treatment and extended detention without trial.

-

29 April 2024

at

12:15pm

adamppatch

says:

@

Delaide

That reflects an incredibly parochial mindset. US intelligence claimed he was traveling in Afghanistan since mid 2001 and that he was captured by Afghan forces in late 2001. The US invasion began on October 2001.

-

30 April 2024

at

6:25am

Delaide

says:

My parochial mind can’t properly grasp your logic but thank you for giving us the US case against Mansoor. It’s detailed enough to indicate that he may not have been an innocent abroad, as he seemed to have been cast in Ms Thompson’s post, though extradition hardly seems warranted. I’m tempted to ask what Mansoor says he was doing .., no, wait .., I withdraw the question!

-

30 April 2024

at

2:56pm

adamppatch

says:

@

Delaide

My point in giving the US case was that you said "it would be nice to know...". If you were really interested in an answer, one was readily available. This suggests that you weren't all that interested in finding information. More in attempting to provide some degree of qualification to the clear injustice suffered by those held at Guantanamo Bay.

-

1 May 2024

at

11:00am

Delaide

says:

@

adamppatch

An “answer was readily available”? I don’t know how I was meant to draw that conclusion from the original article, with all the references to information being classified and Mansoor himself being bewildered. As for all the assumptions you made about me, I deny them, but of course I would. Can we please leave it there Adam? You’ve made your point and I fear more from either of us would be (even more) tedious.

-

3 May 2024

at

12:35pm

J k Beattie

says:

@

Delaide

I just did a Google search re Mansoor Adayfi and came up with quite a few responses with interesting content.

Read moreNow let's transpose your question to more recent events. Russia began its latest invasion of Ukraine began on 24 February 2022. At that time, there were many thousands of non-Ukrainians traveling in Ukraine, despite the recent increase in tensions and the longstanding conflict between the two countries. Some of those non-Ukrainians may have been in the territories quickly overun by Russia. If they had been swept up by Russian forces and then tortured, would you think "it would be nice to know why they were travelling, at such a dangerous time, in Ukraine". Or is it only muslim men in countries that don't sound like tourist hot spots to you (despite the natural, cultural and religious richness of Afghanistan) that must have provide legitimate reasons for being found far from home?

As it happens, the US gave its own account of what it thought he was doing there in a 2015 hearing:

Mansur Ahmad Saad al -Dayfi ( YM - 441) probably was a low-level fighter who was aligned with al - Qa'ida , although it is unclear whether he actually joined that group . He traveled to Afghanistan in mid - 2001 trained at an al- Qa'ida camp, and was wounded by a coalition airstrike after the 9/11 attacks. Afghan forces captured him in late 2001 and imprisoned him at the Qala- i-Janghi fortress , where he probably did not play a significant role in the subsequent prisoner uprising. YM - 441 has admitted to - and later denied involvement al-Qa'ida , and he probably has exaggerated his involvement in and knowledge of terrorist activities during some of his interrogations. Reporting from other sources suggests that he did not play a senior role in terrorist activities, and no al Qa'ida leaders or

associated figures have identified him as a member of al Qa'ida.

So, if you really thought it would be nice to know, the US government provides an easily accesible answer to your question. Then again, given how little uncertainty there is in their account, quite possibly they were thinking along similar lines as you (and many other US government agencies): "well, we don't have any evidence, but he's a young, brown man far home, so he must have been up to something."

The US claims that he was "probably was a low-level fighter who was aligned with al Qa'ida, although it is unclear whether he actually joined that group." That may or may not be true, though it's shocking that that's the best they can come up with after 14 years of detention, interrogation and torture.

By this stage, whether he was ever interested in carrying out violence (possibly including but not limited to defending Afghanistan from US invasion) is entirely and utterly immaterial. No matter what his intentions were in traveling to Afghanistan, he has suffered an enormous injustice at the hands of the US government. No inquiry into his intentions can have the slightest bearing on that.

In the matter of distance, it seems that Yemen to Afghanistan is about the same distance as California to New York. Or, if you'd like somewhere abroad, California to, say, Guatemala.